Thoughts on the future of the real estate market of Tokyo

15 Jan 2023 | #japan | #money | #housingThis is a continuation of my previous post on buying vs renting in Tokyo

The future resale price of a property depends on demand: are there going to be people willing and able to purchase it? Let’s look into the forecasts affecting this. I will try my best to use official (government) statistics and forecasts, even if these are a few years outdated.

Japan

The population of Japan is declining since 2008, with the population aging rapidly (40% of total private households are elderly households (private households with household members aged 65 years old and over)). Moreover the number of households is predicted to peak in 2023 and then decline. (The delay compared to population peak is due to households getting smaller in recent years.)

Wage growth has been minimal during recent years. From 2012 to 2018 the year over year average income per household changed: -1.55%, +2.46%, +0.65%, +2.71%, -1.54%, +0.13%.

Tokyo

The population of Tokyo is still growing and expected to peak around 2030. The ratio of elderly people (65 year+) is currently 23%, and it is expected to grow to more than 30% by 2045. A different, 2019 study titled “Household Projections for Japan by Prefecture : 2015-2040” predicts that the number of households within Tokyo will follow a similar trend.

Predictions from the two studies above:

| 2015 | 2020 | 2025 | 2030 | 2035 | 2040 | 2045 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total population of Tokyo | 13,515,000 | 13,733,000 | 13,846,000 | 13,883,000 | 13,852,000 | 13,759,000 | 13,607,000 |

| Change from 5 year prior | +1.61% | +0.82% | +0.27% | -0.22% | -0.67% | -1.10% | |

| Population over 65 | 3,066,000 | 3,215,000 | 3,272,000 | 3,422,000 | 3,675,000 | 3,996,000 | 4,176,000 |

| Share of elderly population | 22.69% | 23.41% | 23.63% | 24.65% | 26.53% | 29.04% | 30.69% |

| Number of households | 6,691,000 | 6,922,000 | 7,054,000 | 7,107,000 | 7,097,000 | 7,019,000 | |

| Change from 5 year prior | +3.5% | +1.9% | +0.8% | -0.1% | -1.1% |

So the population as well as the number of households in Tokyo is expected to peak in 10 years and then decline, while the population continues to age. This will very likely put strain on the pension system: lower pension being paid, while the working generation will get taxed higher. Overall this will likely result in lower buying power for real estate.

Moreover I’m looking for a family-size home (3-5 rooms), and the need for those will likely decrease faster as the number of young people with families fall.

Side note on prefectures around Tokyo: the above statistics are concerned only about the prefecture of Tokyo, while many people who work in Tokyo commute from neighboring prefectures like Chiba, Saitama and Kanagawa. However the number of commuters outside of Tokyo only accounted for 18% of the population of Tokyo in 2010, so using Tokyo numbers is likely a good enough approximation for the Greater Tokyo Area.

Market in recent years

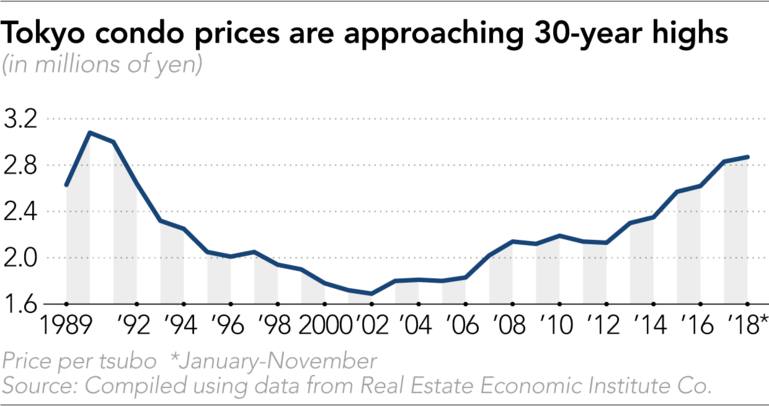

The property market in Tokyo has been pretty hot in recent years reaching levels last seen during the bubble in the ’90s:

.

.

An IMF study on the Japanese real estate market

In 2020 the International Monetary Fund published a study titled Demographics and the Housing Market: Japan’s Disappearing Cities on the present and future of the Japanese real estate market. Below are some of their findings that I found interesting.

When population falls, house prices fall faster

We find that there exists a positive correlation between population growth and house prices—a 1 percent increase in population growth is associated with a 5 percentage points increase in house prices. Furthermore, we find that this positive correlation embeds a nonlinear relationship between population growth and house price changes. Consistent with the durable housing model (Glaeser and Gyourko (2005)), the magnitude of house price decreases associated with population decline is larger than the magnitude of house price increases associated with population increase of the same magnitude in absolute terms. This non-linear relationship is time-varying. Using the same data looking at just the last ten years, the positive correlation between an increase in population and an increase in house prices has weakened, although the positive correlation between negative population growth and the decline in house prices remains.

Emphasis mine.

This can be largely explained by the fact that when the demand is going up, then developers can build new buildings, so the supply can increase too. However when demand is falling, supply will not fall so quickly. This is likely more true for countries with older houses, as in Tokyo very few people would want to live in a 20+ year old house that hasn’t been renovated recently, but based on this study it is also true for Japan in general.

Self-fulfilling prophesies

The linkage between population loss and a housing price decline could lead to a vicious cycle—residents expecting a housing price decline may sell their houses and have less incentives to own houses, which will add to already-existing oversupply for houses and create further downward pressures on housing prices.

This is the same thinking as looking at a hot market and expecting it to keep going up. Considering the significant portion of foreign investment into the Tokyo real estate, these investors might move fast on signs of prices dropping speeding up the process.

Moving to the city abroad

House price declines directly affect local governments by reductions in tax revenue from housing transactions. It would produce the second-round effect, quality and quantity of social spending in the area. This might accelerate population outflows, which further exacerbates the housing market and prices.

The article discusses this issue in relation to young people moving to large cities, however if the same situation would to come for Tokyo in 20-30 years, then highly skilled people will consider moving abroad, the same way many of their parents and grandparents moved from their villages to the cities. The same way this accelerated the real estate decline on the countryside, this can result in a similar effect for Tokyo.